The Modern guide to fertility drugs for ovulation induction

Reviewed by Jenn Conti, MD, MS, MSc,

Written by Talia Shirazi, PhD

last updated: Oct 08, 2020

11 min read

Here's what we'll cover

While some people with ovaries regularly ovulate, there are others who either ovulate irregularly or not at all (for example, some of the 1 in 10 ovary owners with polycystic ovary syndrome). Since ovulation is key to getting pregnant, many people end up using ovulation-induction treatments to conceive.

Ovulation-inducing meds were invented in the 1960s. They provide a boost to follicular development and ovulation for people who are not regularly ovulating naturally. (Reminder: follicles are the tiny sacs that nourish and hold developing eggs, which get released during ovulation.)

In this post, we’ll give you the rundown of the current ovulation-inducing prescription meds available on the market, like clomiphene citrate (Clomid) and letrozole (Femara).

We'll also discuss medications that aren’t really considered "fertility drugs" but may affect reproductive function for certain people (such as metformin). Plus, we'll give you a rundown of non-FDA-approved, non-prescription supplements that claim to support ovulation.

While there’s no “magic bullet” when it comes to meds for follicular growth and ovulation, we hope this post shows you that thanks to science, you’ve got options.

The main takeaways

Clomiphene citrate (Clomid) and letrozole (Femara) are usually the first line of ovulation-inducing defense. These drugs are taken orally, are cost effective, have minimal side effects compared to other fertility drugs, and work for most people (roughly 80%!).

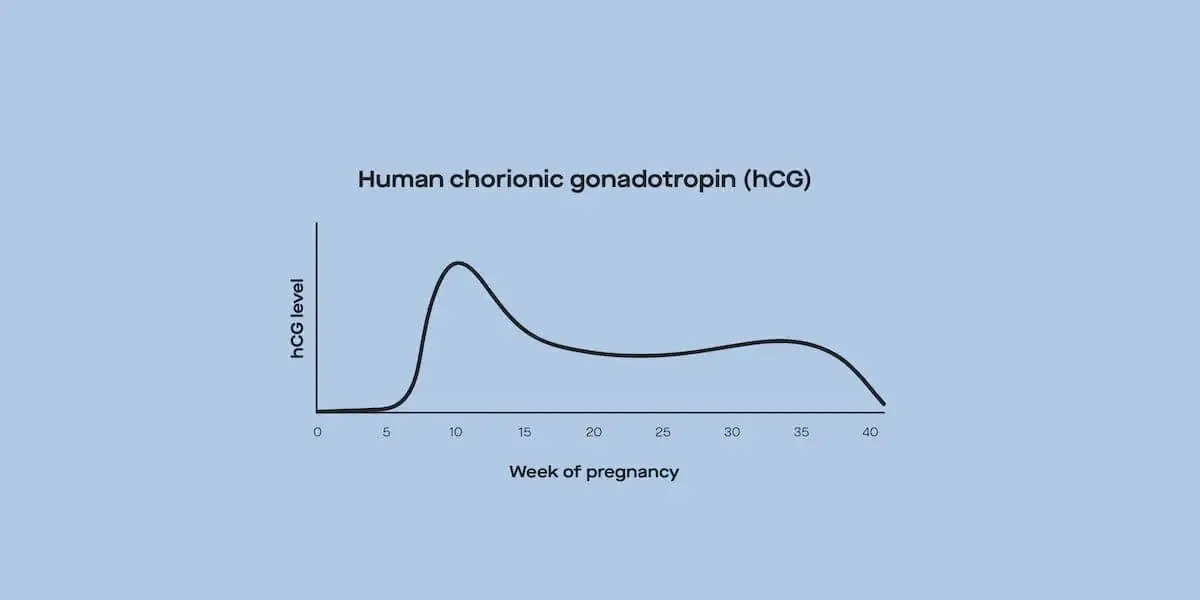

Injectable gonadotropins — a fancy word for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) — can induce follicular growth and ovulation. They’re injectable, differ slightly in their risks and side effects as compared to oral meds, and are more costly. Because of this, these are not used as a first option outside the context of fertility preservation and in-vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures.

There is growing evidence to suggest that inositol (or myo-inositol) can improve reproductive outcomes for some people with PCOS.

Supplementing with progesterone is not routinely done by most physicians — in some cases it may be used during the luteal phase (i.e., after ovulation) to help support the endometrium as it tries to implant the embryo. However, there isn’t compelling evidence that doing so significantly improves pregnancy rates.

Keep in mind: Doctors will always look for the reason for irregular or absent ovulation before using ovulation-inducing medications. Knowing about your own ovulation patterns, reproductive hormones, and general health sets you up for a well-informed conversation with your doctor about whether prescription fertility drugs may be right for you.

Who should consider taking fertility drugs?

Ovulation issues (like irregular ovulation or no ovulation at all) cause about 25% of fertility issues in people with ovaries. Here’s how ovulation affects conception: follicles in the ovaries release eggs each month (aka ovulation) which then travel through the fallopian tube, where (if conception occurs) they most frequently meet sperm and unite to form a zygote, then embryo. If a follicle doesn’t mature (determined by the hormones in the brain and ovary that synchronize the ovulation process) and an egg isn’t released in a given cycle, the chances of natural conception are zero. You can’t have conception without an egg.

People who are tracking their cycles and ovulation likely have a good idea of their ovulation patterns. For people who are ovulating regularly, follicle-growing and ovulation-inducing meds would only be recommended in cases of infertility, where they may help grow and release more than one egg at a time, improving the chances of conception, but also that of multiple pregnancy.

But what about people who don't consistently detect ovulation? Some may monitor their urinary LH levels and never see a surge, and/or keep tabs on their cervical mucus but not notice any changes across the cycle. Before assuming ovulation-inducing meds are for you, it’s important to rule out conditions that indirectly affect reproductive function. For example, high levels of prolactin and thyroid disorders (like hypo- or hyperthyroidism) can both disrupt ovulation — and treating those conditions directly can lead to more regular ovulation patterns. It’s also the case that for some conditions (like hypothyroidism), not treating the underlying condition can also negatively affect pregnancy outcomes.

The two most common fertility drugs: clomiphene citrate (Clomid) and letrozole (Femara)

Clomiphene citrate (aka Clomid and Clomiphene) and letrozole (aka Femara) get a lot of attention when it comes to follicle-growing and ovulation-inducing drugs, and for good reason: they’ve been around for a long time (in the case of Clomid, since 1967!), they’ve been intensely studied, their side effects are minimal (usually), they’re easy to take, they’re relatively cheap, and most importantly — they work for a solid chunk of people who take them.

How clomiphene citrate and letrozole work

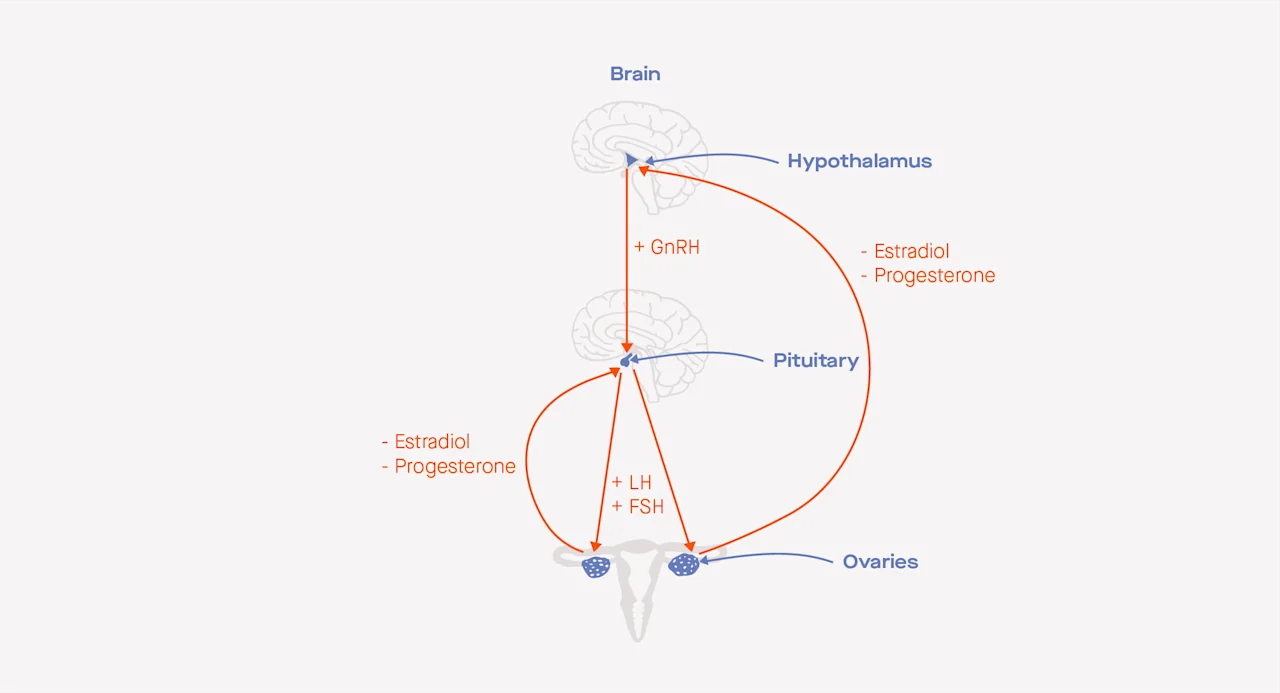

Clomiphene citrate and letrozole have a similar mechanism of action —- both of them “trick” the brain into thinking there’s less estradiol (a form of estrogen) floating around using slightly different approaches. Here’s why that’s important: Estradiol usually tells the brain to dial back on its production of the two gonadotropin hormones crucial in follicular development and ovulation, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

What exactly are gonadotropin hormones? They’re the ones the pituitary gland releases to signal the release of other hormones from the gonads (either the ovaries or testes). In humans, the main gonadotropins are FSH and LH — the hormones clomiphene citrate and letrozole trigger an uptick in these gonadotropins. (Keep this info in mind: It will come in handy once we get to the injectable gonadotropins section.)

The hormonal feedback loop between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the ovaries before ovulation includes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), estradiol, progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The “+” hormones send signals to other organs to stimulate the production of additional hormones, whereas the "-" hormones send signals to other organs to inhibit the production of additional hormones.

Back to clomiphene citrate and letrozole: When the brain interprets less estradiol input, it signals the release of higher levels of FSH, which then leads to more follicular development in the ovaries.

Reproductive endocrinologists and infertility specialists (aka REIs) will typically have people start taking clomiphene citrate or letrozole between the second day and fifth day after the onset of menses, and prescribe a five-day dose.

People who are completely anovulatory (they never ovulate) may start taking these pills on any cycle day. Alternatively, people who are completely anovulatory and people with irregular cycles may have a progesterone-induced “period” (aka withdrawal bleed) and start taking pills a few days after their bleed begins. We use quotations there because a progesterone-induced bleed is your body’s response to the rise and then rapid fall of synthetic progesterone levels, while a natural period is the result of a dissolving corpus luteum cyst (formerly the main follicle that released the egg during ovulation), which is the main progesterone-producing structure in the ovary.

Just like oral contraceptives, doctors recommend you take clomiphene citrate and letrozole at the same time of day every day.

Starting doses of these medications are usually on the lower end (50mg for clomiphene citrate, 2.5mg for letrozole) because lower doses come with fewer side effects. It’s common for doctors to monitor follicular development via ultrasound while these meds are being taken: Not enough follicular development suggests the medication dose should be increased, while too much follicular development suggests the dose should be decreased or stopped altogether, and your doctor may recommend you skip that cycle to lower the chance of multiples.

Success rates

We gave it away at the beginning of this section, but we’ll say it again: Clomiphene citrate and letrozole are considered very effective given their cost and low potential for serious side effects.

Let’s talk clomiphene citrate first. Once doctors and patients get the dosage right (which might require a bit of trial and error), about 80%

That’s a big deal: 8 in 10 people who take Clomid, given they were appropriate candidates for its use, will have a well-developed follicle and ovulate.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) patient guidelines suggest that people look beyond Clomid if they haven’t conceived after six clomiphene citrate-induced cycles. If conception hasn’t happened after six cycles, there could be something other than follicular growth and ovulation (like obstructions in the fallopian tubes or uterus) that’s getting in the way of a pregnancy.

While clomiphene citrate was traditionally the first line of defense for basically all people who didn’t ovulate, a study published in 2014 changed the game for people with PCOS. In a large, double-blind trial of 750 people with PCOS receiving either letrozole or clomiphene citrate, letrozole came out on top: live births were higher in the letrozole group (28%, versus 19% in the clomiphene citrate group), frequency of ovulation was higher in the letrozole group (62%, versus 48% in the clomiphene citrate group), and rates of pregnancy loss and twin pregnancies didn’t differ between the two. Because of this study and others that came after it finding similar results, doctors often recommend letrozole for people with PCOS.

Clomiphene citrate and letrozole have similar results in people who don’t have PCOS.

Clomiphene citrate and letrozole side effects

Now for the not-as-rosy parts: the side effects. Serious side effects with low clomiphene citrate and letrozole doses are very rare, and typically disappear within a few days after stopping these meds.

The most commonly reported side effect of clomiphene citrate is mood swings, which is reported by about 64-78% of users. It’s also normal for people on clomiphene citrate and letrozole to experience hot flashes, fatigue, and dizziness.

Meta-analyses (i.e., papers that combine relevant data from all past papers and analyze it all together) suggest clomiphene citrate use is associated with a thinner endometrium; because a healthy endometrium is necessary for implantation, a thin endometrium isn’t exactly an outcome you’d want if you’re trying to conceive. Because of the slight difference in the mechanisms of action for clomiphene citrate and letrozole, letrozole doesn’t negatively impact endometrial development the way clomiphene citrate does.

But, an important caveat: Despite the fact that letrozole doesn’t have negative effects on endometrial development while clomiphene citrate does, live birth rates don’t statistically significantly differ between the two meds for people who don’t have PCOS. This means a thinner endometrium with clomiphene citrate use may not be much to worry about, though some doctors will prescribe add-on medications meant to boost development of the uterine lining (keep reading for a full section on these sorts of add-on medications!). In general, these add-on medications themselves won’t help you ovulate, but in theory are meant to boost your chances of conception if ovulation occurs.

While at one point in time there was concern that babies born as a result of clomiphene citrate or letrozole-induced cycles were more likely to be born with developmental abnormalities, we now know this is not true — there is no evidence for harmful developmental effects of either med.

Metformin, trigger shots, and other add-on meds

Clomiphene citrate and letrozole are the main two oral ovulation-inducing meds your doctor may prescribe, but that doesn’t mean your options stop there. Here, we’ll list the most commonly prescribed “add-on” medications to fertility drug regimens.

1. Metformin: The same medication commonly prescribed for people with insulin resistance also makes our list for fertility drug regimen add-ons. Metformin is most likely to be helpful for people who have insulin resistance (which is seen in up to 70% of people with PCOS). But, the evidence is mixed on whether taking metformin will significantly affect ovulation.

One large study of people with PCOS compared metformin alone, clomiphene citrate alone, and the metformin + clomiphene citrate combo. While 7% of people in the metformin-alone group ovulated, this rose to 23% in the clomiphene citrate group, and was not statistically significantly higher in the clomiphene citrate + metformin group (27%). The takeaway? Metformin might help some people ovulate, but it likely won’t do all that much for most people.

2. hCG trigger shots: An hCG or LH surge is necessary for ovulation to happen. While many people using clomiphene citrate or letrozole will ovulate without these added meds, there are some reasons for their use. Since hCG trigger shots induce ovulation within about 36 hours, they can be used to more precisely time intercourse or intrauterine insemination (IUI) to maximize chances of conception. Most of the time, they’re used on patients going through IUI.

3. Progesterone: Progesterone is used in some cases during the luteal phase (i.e., after ovulation) to help support the endometrium as it tries to implant the embryo. However, there isn’t compelling evidence that doing so significantly improves pregnancy rates and it is not done routinely by most physicians.

Injectable gonadotropins

Injectable gonadotropins are mostly used during egg retrieval for fertility preservation or IVF. Gonadotropins are the hormones that signal the release of hormones from the ovaries or testes. While oral meds like clomiphene citrate and letrozole increase the body’s own FSH and LH production, injectable forms of FSH and LH supplement these (think of it as bypassing a step in the pathway). Because of their potency, doctors will monitor your body closely to get the dosing just right.

Some injectable gonadotropin preparations contain just FSH or just human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), while others might be a combo of FSH and either LH or hCG. Follistim, Gonal-F, Bravelle, and Fertinex are common FSH-only injections, and Ovidrel, Novarel, and Pregnyl are common hCG-only injections. Commonly used FSH-hCG combo meds are Menopur, Novarel, and Pregnyl.

How they work and how they’re used

Similar to clomiphene citrate and letrozole, injectable gonadotropins start being used during the first few days of a menstrual cycle. These meds will usually be used for 7-12 days. Why such a wide range? Since your body is not producing any of its own reproductive hormones, you will need to take medication all the way until the day of a trigger shot, which will induce ovulation.

A first ultrasound is typically done 4-5 days after the beginning of treatment, and every 1-3 days thereafter. The dosing will depend on whether the goal is to produce a single developed egg or several — during IVF (which is when injectable gonadotropins are most commonly used), the goal with injectable gonadotropins is to produce as many developed eggs as possible to safely retrieve while minimizing side effects.

Success rates

Injectable gonadotropins, when monitored and administered correctly, are very effective at inducing ovulation. Some studies of clomiphene citrate-resistant people suggest that up to 90% will ovulate when using injectable forms of FSH and hCG, while others pin the ovulation rate between 60% and 80%.

Small studies of people with PCOS suggest ovulation rates upwards of 90% in response to gonadotropin treatment. That being said, because these meds are overwhelmingly used in the context of egg freezing and IVF procedures, “success” is usually measured by how well they aid in the development of a group of eggs, not just a single one.

Side effects of injectable gonadotropins

Possible side effects for injectable gonadotropins are mostly mild and similar for those of clomiphene citrate and letrozole: mood swings, fatigue, and hot flashes are sometimes reported.

Perhaps the most serious potential side effect for injectable gonadotropins is something called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). In more mild cases of OHSS, the ovaries become swollen and painful; in more serious cases (about 2% of all cycles), it’s serious enough to warrant hospitalization. Testing reproductive hormones like anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) prior to starting on injectable gonadotropins can help doctors determine a dose that may reduce your risks of developing OHSS.

How fertility drugs lead to increased chances of twins or multiples

All the ovulation-inducing methods we’ve covered so far can lead to increased chances of twins and higher-order births (aka multiples).

Since both clomiphene citrate and letrozole increase the hormones directly responsible for follicle maturation and ovulation, hyperovulation (ovulating multiple eggs) is a possibility. While twins occur in about 1 in 250 pregnancies (0.4%) where fertility drugs aren’t used, they’ll occur in between 5% and 8% of pregnancies where clomiphene citrate and letrozole are used.

Interestingly, while things like IVF are typically seen as the culprit for higher-order births, use of these fertility drugs actually contributes to a higher percentage of higher-order births than does the use of IVF. In the past, multiple embryos were often transferred during IVF — which contributed to higher-order births. Today, in most cases, most clinics now transfer one embryo, leading to a sharp drop in multiple pregnancies due to IVF.

Hyperovulation and higher-order births are also possible “risks” of injectable gonadotropins. We say “risk” in quotation marks because the goal of most cycles where injectable gonadotropins are used is to actually produce as many developed eggs as possible for retrieval and freezing. In cases where this isn’t the goal, like when these meds are being used to jumpstart follicular development and ovulation, up to 32% of cycles resulting in a pregnancy are twins or higher-order births (about two-thirds of those multiple pregnancies are twins).

What’s the deal with non-prescription “fertility supplements”?

We’ve previously written about some of the issues with fertility supplements you can buy without prescription, but the info bears repetition: If you have been monitoring your cycles and are not ovulating consistently, your best bet is a prescription your doctor can prescribe, and not a supplement you can buy on the internet.

Diligent investigative work of 39 so-called “fertility supplements” done by the Center for Science in the Public Interest found literally zero scientific evidence to support any of the claims made by manufacturers, and when the manufacturers were asked for proof their product works, they overwhelmingly pointed to customer reviews. Customer reviews are great! But they aren’t science (i.e., you can’t prove that something didn’t just coincidentally work for someone). Because of this, you’re better off allocating your resources toward medications that have been proven, by literally decades-worth of studies, to work (like the ones discussed above).

Another issue with supplements is that they’re not regulated by the FDA, so there’s a lack of standardized oversight in the manufacturing safety of these products.

There’s one noteworthy exception: inositol for people with PCOS

Inositol (or myo-inositol) is a compound used as an add-on to treatment for a curiously wide range of conditions, from Alzheimer’s to diabetes-related nerve pain. There’s also growing evidence to suggest it can improve reproductive outcomes for some people with PCOS. More specifically, since inositol can ameliorate some of the effects of insulin resistance, its effects in the body are similar to those of metformin.

Though better data is needed, a recent meta-analysis found that as compared to placebo (aka a sugar pill with no active ingredient), inositol was associated with more frequent ovulation in people with PCOS. When putting inositol head to head with metformin, some studies found no differences in how effective these meds are in promoting ovulation and menstrual cycle regularity.

The bottom line

There are many FDA-approved treatment options out there to kick-start follicular growth and ovulation for people who aren’t ovulating regularly. Tracking your cycles to understand whether you’re regularly ovulating is a great first step; for those who aren’t, the next important step is figuring out whether any underlying conditions may be the culprit.

Knowing more about your ovulation patterns, general health, and hormone levels will help you start a well-informed conversation with your doctor about whether prescription fertility drugs are right for you. Getting to a fertility drug regimen that works for you might require a bit of trial and error, but research shows it’s ultimately wiser to continue working with your doctor to find the right prescription versus relying on “fertility supplements” you might see online.

This article was reviewed by Dr. Jennifer Conti, an OB-GYN who serves as a Modern Fertility medical advisor and is also an adjunct clinical assistant professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. It was also reviewed by Dr. Eduardo Hariton, an OB-GYN and reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California in San Francisco.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.